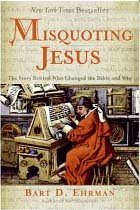

Misquoting Jesus by Bart Ehrman ****

In his introduction to Misquoting Jesus, Bart Ehrman gives a brief account of his own personal journey from unquestioning acceptance of the New Testament text to his present view of it as a “very human book.” He then proceeds to show the reader exactly why we cannot know in many cases what the original text was, the ways in which texts are changed, accidentally or intentionally, and gives several examples of verses whose “original” content is disputed.

While I suppose that the history of the development of textual criticism and the discovery and comparison of various manuscripts over the past several centuries is necessary to the overall thrust of the book, this was the part that I found least interesting although the sheer number of discrepancies (many relatively minor) is eye-opening. However, I believe that two sections of the book are particularly helpful to the general reader in understanding why the differences exist. Chapters 1 and 2 deal with the formation of the Christian canon as well as the mechanics of scribal transmission and that of the New Testament in particular. Ehrman stresses the fact that many of those who were copying the earliest texts of these books were not trained scribes and in many cases may have been barely literate – something that the average person probably doesn't even consider in our modern world of widespread literacy, photocopying and "cut and paste." Chapters 6 and 7, on the other hand, look at the motivations for intentional changes, which were often pure; that is, in many cases the scribe may have believed that he was correcting an earlier mistake or clarifying a text that might otherwise be used to support “heretical” beliefs.

Many readers, I suspect, will be upset to discover that there is a consensus among textual critics that one of the most famous stories in the Gospels, that of the woman taken in adultery, is not original to the Gospel of John. However, as Ehrman points out, that does not mean that it is not a real tradition; like many parts of the Bible that seem out of place, it may have been so well-known and powerful that it had to find its way into the text somehow.

It has always struck me that the belief in the inerrancy of the Bible (or anything made or transmitted by human hands) comes dangerously close to the sin of idolatry. I hope that this introduction to textual criticism, which is carried out by many scholars because of their love of the text and a desire to get as close to the original as possible, will inspire many with a new respect for the many people who did create it and transmit it. God does work through human beings, after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment